Keywords:

By Nastya Yeska

Food intolerance or sensitivity to many common foods, such as gluten, dairy or other products, appears to be on the increase. This begs the question: does food intolerance really exist, or is it simply a trendy fad in today’s health-conscious society? In this new blog series we start by reviewing the science behind food intolerance, outline its potential causes, and investigate how it could be reliably diagnosed and treated using IgG-based tests such as ELISA.

Food intolerance and IgG testing.

Allergy or intolerance?

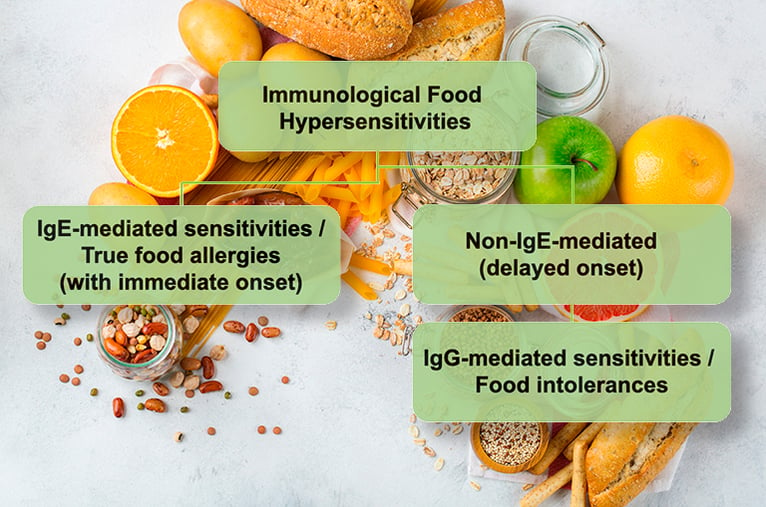

Allergies, such as reactions to specific proteins in wheat or milk, involve the immune system, and can be life-threatening. In general, true food allergies are IgE-mediated. Symptoms, which usually kick in within minutes of eating a problem food, can include vomiting, swelling of the lips and face, a rash, or asthma-like symptoms, including wheezing, and a blocked or runny nose.

Wheat allergy is either an IgE-mediated or non-IgE-mediated allergic reaction to wheat proteins.1 The result can be life-threatening and can lead to an anaphylactic reaction. The prevalence of wheat-based food allergy is likely in the range of 0.2% to 1% globally.2 Children have a higher prevalence of wheat allergies compared to adults and are more likely to develop an allergy if wheat is introduced after 6 months of life.2,3 Children typically outgrow their allergy, and about 65% have a resolution by the age of 12.4

We also often hear of celiac (coeliac) disease, a non-IgE-mediated immune response which affects 1% of the population globally.5 Celiac disease is an autoimmune condition that causes serious harm if sufferers eat even small amounts of gluten-containing foods. Antibodies are generated against the gluten, but these also attack cells lining the gut, resulting in malnutrition.

Food intolerances, on the other hand, tend to generate symptoms such as bloating or abdominal pain, and these set in more slowly. Due to this delayed reaction, usually 24-72 hours after food intake, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between the symptom and a specific food. Figure 1 outlines the differences in the immune response between allergy and intolerance

The mechanism of food intolerance is thought to occur through chronic stimulation of the gastrointestinal tract with certain food ingredients (food antigens), which impairs its basic function, potentially leading to chronic inflammation and greater permeability of the gut mucosa. Indeed, in a broader context, intestinal permeability has recently been reviewed as a new target for disease prevention and therapy, including for irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), a form of food intolerance.6

Irritable bowel syndrome and IgG4 levels

IBS is a common disorder that affects the large intestine. Symptoms include cramping, abdominal pain, bloating, gas, diarrhoea or constipation. IBS patients commonly report that specific foods trigger their symptoms, and up to 60% of patients report worsening of symptoms after food intake, with 84% linking the symptoms to a single food type.7

How can we measure the immune reaction in IBS and potentially highlight a problem food type? One way could be to use IgG (immunoglobulin G) testing, which looks for antibodies against food substances (antigens) in the blood. Specific serum IgG4 antibodies have been reported in celiac disease, dermatitis or atopic eczema, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and IBS, although in the absence of a pathology, it should be recognised that the presence of specific IgG antibodies is also a normal immune response to the ingestion of the foods concerned.8,9

Amongst the 4 subclasses of IgG antibodies, IgG4 reactions take place in the gut during repeated exposure to food antigens. Zar et al. reported elevated serum IgG4 levels to some foods in IBS patients.10 In that study, no significant differences in IgE levels were observed between IBS patients and healthy controls, and it was reported that food elimination based on IgG4 levels improved symptoms in IBS patients.11

More recently, Lee and Lee compared food-specific IgG4 levels to common food antigens between patients with IBS and healthy controls, and found elevated food-specific serum IgG4 titres to common food antigens in patients with irritable bowel syndrome, compared to healthy controls.12

In addition, a serological investigation of food-specific IgG antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs: Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis) demonstrated a high prevalence of serum IgG antibodies to specific food allergens in patients with IBD.13 It was concluded that IgG antibodies may potentially indicate disease status in clinical diagnosis, and could be used to guide diets for patients.

Diagnosing food intolerance using IgG4 tests

Now that we have established that food-specific IgG4 levels can be an indicator of food intolerance in specific pathologies, what can we do with that information?

The idea of doing an IgG4 test is to identify which foods might be triggering an immune response in the patient that may be associated with IBD or IBS.14,15,16 It follows that the treatment will involve the systematic elimination of the foods that trigger that response. This is followed by a controlled reintroduction of the foods, with concurrent close monitoring of the symptoms.

Patients are generally asked to eliminate the indicated foods from their diet for a period of 12 weeks. They also receive nutritional advice on eliminating the different foods. Let us take the example of a typical IBS study.16 Symptoms are assessed using a validated IBS questionnaire scoring system, which scores pain, distension, bowel dysfunction, general well-being, and includes a global IBS rating.17 Data on these measures are recorded at baseline, and after 4, 8, and 12 weeks of the dietary intervention period.

At the end of 12 weeks, patients resume consumption of the foods they had been advised to eliminate, in an oral challenge that helps assess the effect of reintroduction. Patients are then reassessed after four weeks using the same measures, and the result is compared with their scores from the end of the elimination phase.

The concurrent measurement of IgG4 levels corresponding to the eliminated food at each stage would be a useful addition to the IBS scoring system. It could then easily be determined whether the IgG4 level corresponding to the food decreases on its elimination from the diet, and then whether the challenge with the eliminated food results in a higher level of the same IgG4, a strong correlation confirming that the food intolerance has been successfully identified.

Conclusion: is there a role for IgG4 testing in IBS and food intolerance?

IgG4 testing may not be recommended for diagnosing food intolerance in the first instance, before the patient has undergone other investigations, since IgG4 can simply be an indicator of tolerance to a specific antigen. However, there is a definite role for IgG4 testing when it comes to diagnosing and treating pathologies that are associated with elevated levels of specific IgGs, such as Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis and irritable bowel syndrome. With that in mind, discover the challenges in developing the ideal IgG4 test by subscribing to the next blog in our series.

References

- Pasha I, Saeed F, Sultan MT, Batool R, Aziz M, Ahmed W. Wheat Allergy and Intolerance; Recent Updates and Perspectives. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2016;56(1):13-24.

PubMed ID: 24915366

DOI: 1080/10408398.2012.659818. - Cianferoni A. Wheat allergy: diagnosis and management. J Asthma Allergy. 2016;9:13-25. PubMedID: 26889090 DOI: 10.2147/JAA.S81550

- Poole JA, Barriga K, Leung DY, Hoffman M, Eisenbarth GS, Rewers M, Norris JM. (2006) Timing of initial exposure to cereal grains and the risk of wheat allergy. Pediatrics, 117(6), 2175-82. PubMedID: 16740862 DOI: 10.1542/peds.2005-1803

- Keet CA, Matsui EC, Dhillon G, Lenehan P, Paterakis M, Wood RA. (2009) The natural history of wheat allergy. Ann. Allergy Asthma Immunol.,102(5), 410-5. PubMedID: 19492663 DOI: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)60513-3

- Parzanese I, Qehajaj D, Patrinicola F, Aralica M, Chiriva-Internati M, Stifter S, Elli L, Grizzi F. (2017) Celiac disease: From pathophysiology to treatment. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol., 15;8(2), 27-38. PubMedID: 28573065 DOI: 10.4291/wjgp.v8.i2.27

- Bischoff, S.C., Barbara, G. et al. (2014) Intestinal permeability – a new target for disease prevention and therapy. BMC Gastroenterol. 14: 189. Published online 2014 Nov 18. PubMedID: 254075111 DOI: 10.1186/s12876-014-0189-7

- Cuomo, R., Andreozzi, P. et al. (2014) Irritable bowel syndrome and food interaction. World J Gastroenterol., 20(27): 8837–8845. Published online 2014 Jul 21. PubMedID: 25083057 DOI: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8837

- Carr, S., Chan, E., et al. (2012). CSACI Position statement on the testing of food-specific IgG. Allergy, asthma, and clinical immunology : official journal of the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 8(1), 12. PubMedID: 22835332 DOI: 10.1186/1710-1492-8-12

- Gocki, J. and Bartuzi, Z. (2016) Role of immunoglobulin G antibodies in diagnosis of food allergy Postepy Dermatol Alergol. 2016 Aug; 33(4): 253–256. Published online 2016 Aug 16. PubMedID: 27605894 DOI: 10.5114/ada.2016.61600

- Zar S, Benson MJ, Kumar D. (2005) Food-specific serum IgG4 and IgE titers to common food antigens in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol., 100, 1550-1557. PubMedID: 15984980 DOI: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41348.x

- Zar S, Mincher L, Benson MJ, Kumar D. (2005) Food-specific IgG4 antibody-guided exclusion diet improves symptoms and rectal compliance in irritable bowel syndrome. Scand J Gastroenterol., 40, 800-807. PubMedID: 16109655 DOI: 10.1080/00365520510015593

- Lee, H. and Lee, K. J (2017) Alterations of Food-specific Serum IgG4 Titers to Common Food Antigens in Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 23(4), 2093-0879. PubMedID: 28992678 DOI: 10.5056/jnm17054

- Cai, C., Shen, J. et al. (2014) Serological investigation of food specific immunoglobulin G antibodies in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. PloS one, 9(11), e112154. PubMedID: 25393003 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0112154

- Hardman, G. and Hart, G. (2007) Dietary advice based on food-specific IgG results. Nutrition & Food Science 37(1):16-23. ISSN: 0034-6659 DOI: 10.1108/00346650710726913

- Karakula-Juchnowicz, H., Gałęcka, M. et al. (2018) The Food-Specific Serum IgG Reactivity in Major Depressive Disorder Patients, Irritable Bowel Syndrome Patients and Healthy Controls. Nutrients, 10(5), 548. PubMedID: 29710769 DOI: 10.3390/nu10050548

- Atkinson W., Sheldon T.A. et al (2004) Food elimination based on IgG antibodies in irritable bowel syndrome: a randomised controlled trial. Gut;53:1459-1464. PubMedID: 15361495 DOI: 10.1136/gut.2003.037697

- Francis C.Y, Morris J, Whorwell PJ (1997) The irritable bowel scoring system: A simple method of monitoring IBS and its progress. Aliment. Pharmacol. Therap.11:395–402. PubMedID: 9146781 DOI: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1997.142318000.x

Keywords:

About the author

Nastya Yeska

Nastya Yeska joined Tecan in 2017 as a product manager responsible for the Complementary medicine product portfolio, including Food intolerance and Saliva diagnostics. Nastya is part of Global Reagent Marketing & Support Department responsible for delivering ELISA solutions. In 2021, she changed her role to Integrated Marketing Manager.