Keywords:

By Nastya Yeska

IgG and IgG4-based ELISA testing is often recommended to reduce the guesswork in identifying food sensitivities in IBS, IBD and related pathologies, and is the most widely used immunological method.[i]1-4 However, many commercial kits are available, which may have major limitations such as matrix effects, or insufficient specificities, leading to cross-reactions and irreproducible results.3 Here we guide you through five major perceived challenges to setting up reliable IgG-based ELISA food intolerance testing in your lab.

Food intolerance may be at the heart of many cases of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). The challenge is to find which foods could be the root cause.

Challenge #1: which allergens to test

Since there are as many potential sources of food intolerance as there are foods, where should a medical professional start when faced with a distressed patient with IBS, for example? There may be indications from said patient that eliminating wheat or milk from their diets seems to have helped their condition, but when an elimination diet is not carried out rigorously, it is difficult to come to a firm conclusion regarding food intolerance.

A good starting point is to test for the presence of total IgG over a broad range of potential food allergens, which would usually include wheat, cow’s milk, egg white, and perhaps a selection of meat, fruit and vegetables. These will give an indication of total IgG and IgG4 antibody levels for these food groups.

Based on these results, the physician would then be recommended to run a more specialized follow-up screen with further sub-sets of allergens, more tailored to the individual patient. A panel here might consist of a more specific test with fewer allergens, once the specific food groups have been identified. Another approach might be to include up to 280 individual food antigens, across a range of food groups, thus greatly increasing the likelihood of identifying the specific foods the patient cannot tolerate.5,11

The caveat is that the detection of a high level of a specific IgG is merely the start of the patient journey: a definitive clinical diagnosis of food intolerance should never be based solely on the results of a single diagnostic method. Indeed, in vitro evidence of IgG should always be accompanied by a full medical history and analysis of symptoms. The foods in question can then be eliminated from the diet in a controlled way, following detailed nutritionist advice.

Challenge #2: food intolerance testing is difficult

There are two parts to food intolerance testing:

(1) the monitoring of specific physiological criteria associated with the patient’s pathology e.g. for IBS these would be the “Rome” criteria which attempt to standardize the symptoms, such as bloating, bowel habits.6

(2) the monitoring of specific biological markers in parallel at each stage of diagnosis and treatment, which can include looking at IgG and IgG4 levels across a range of foods and is most easily done by ELISA.

Besides ELISA, other methods that have been considered over the years include microarrays, immunoblots, line blots, and rapid tests. However, ELISA tests have stood the test of time when it comes to ease of use, standardization, and throughput, even if the variability between tests and labs when ELISA is set up from scratch has been a major challenge to its adoption by the food intolerance testing community.7

In effect, ELISA tests for food intolerance would be useless without a standardized way of preparing the food antigens used in the tests, together with suitable internal standards, and a notion of what would be “normal” control levels of IgG in the patient samples for the foods tested.

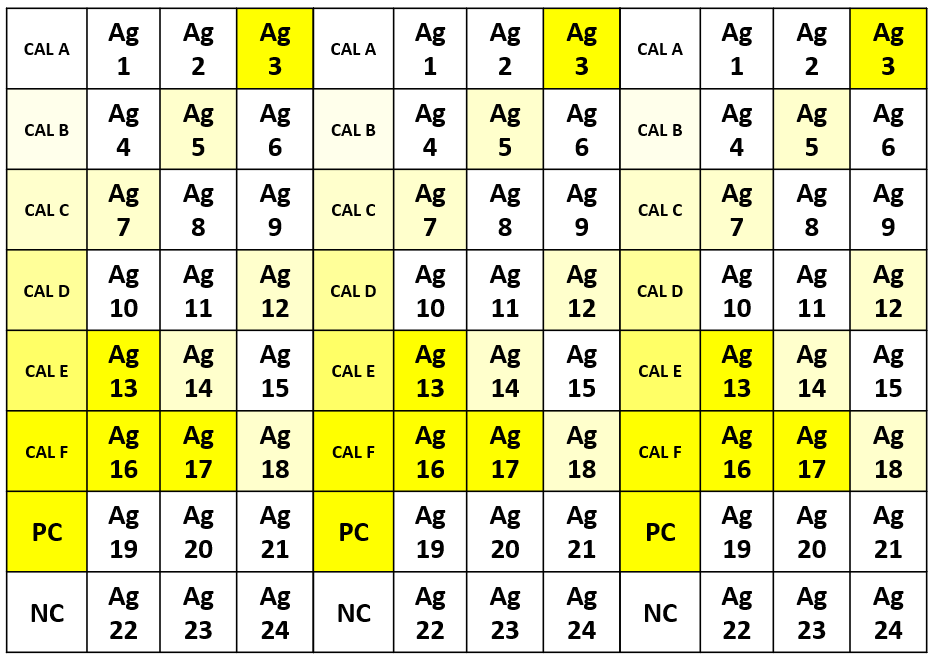

This challenge is being overcome with the development of a broad selection of standardized ELISA tests and processes, including simple sampling procedures. Figure 1 illustrates an example of an ELISA food intolerance test plate, and also gives an indication of how the test result might look.

Figure 1. Example of an ELISA food intolerance test result, with antigens, calibration curve samples and controls plated in triplicate. The darker the yellow, the greater the concentration of IgG in the sample. Ag = Antigens 1-24, CAL = calibration curve sample for quantification, PC = positive control, NC = negative control.

Providers of ELISA IgG food intolerance tests are often unclear about the antigen content of their ELISA plates, making it difficult to recommend a specific provider, whilst also encouraging the proliferation of non-standard tests, which at worst may be of no clinical significance. Some of them may even go so far as to include mixes of antigens for similar food groups e.g., mixture of crustaceans, citrus fruits, poultry.

However, as more food ELISA panels prove themselves to be clinically significant, following their regular use in parallel with the diagnosis and monitoring of specific food-related pathologies, the testing industry will slowly gain in credibility and become more regulated. When that happens, IgG-based tests may be considered to be on a par with other diagnostic criteria.

We are not there yet. However, there are providers out there who can provide specific, defined IgG panels that do give the desired reproducible results. The simplicity of the ELISA protocols that have been developed also means that more practitioners at point of care can set up food intolerance testing themselves or outsource it with confidence.

Challenge #3: IgG-based food intolerance ELISAs are tough to standardize

It is difficult to talk in terms of “absolutes” when it comes to standardization of IgG-based food intolerance ELISAs. In effect, in IgG diagnostics, it is virtually impossible to consider absolute values within strictly defined limits, since the concentration of a food-specific IgG will always be specific to an individual, so cannot be classified in this way. This contrasts with the protocols for true food allergies (immediate onset IgE-mediated sensitivities), where there is a uniform evaluation system, mainly because there is generally a higher IgE concentration that is associated with a particular foodstuff.8

“Standard” reference ranges for blood serum concentrations of total lgG antibodies in the blood are described in the literature.9 These values will not apply to the values determined by IgG-based food intolerance ELISA tests however, since the latter measure food-specific IgG antibodies. Determining reference ranges for food-specific IgG antibodies is simply not possible, due to the high diversity of ingested foods by different individuals.

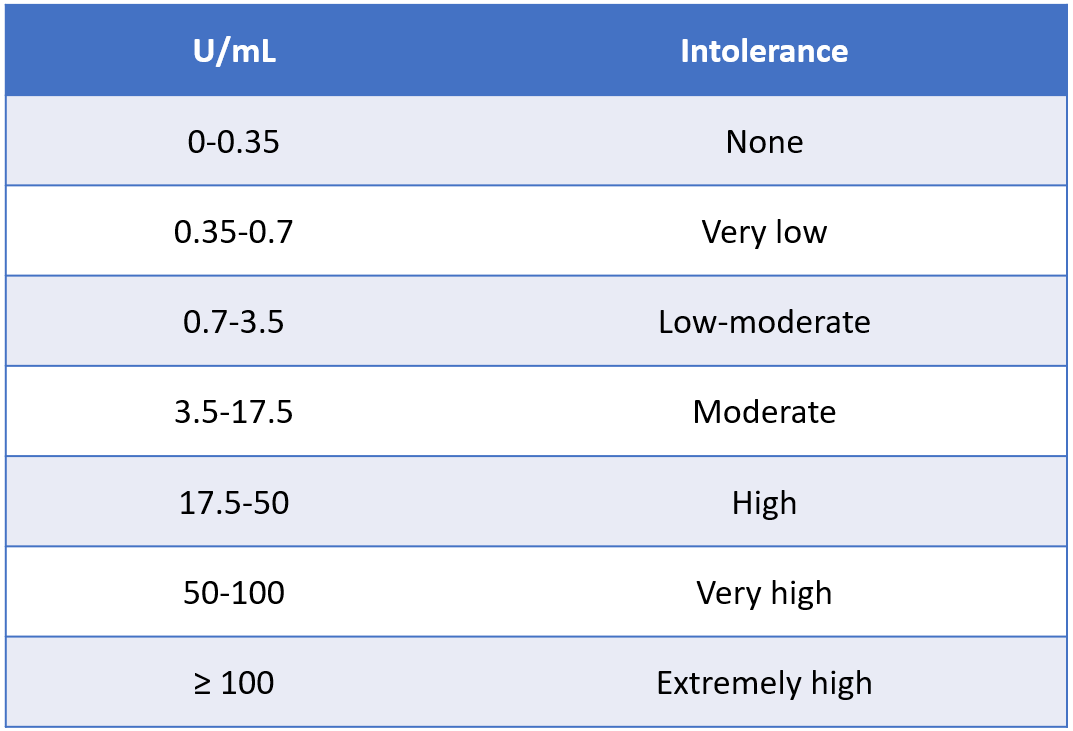

Having said that, one must ascertain a degree of relative reactivity for the different foodstuffs that are tested, and a general overview is given in Table 1.

Table 1. Classification of reactivity, from no or low intolerance, to very high likelihood of intolerance.5

Higher test results (U/mL) indicate a higher concentration of the food specific IgG reacting to the food extracts or extract mixtures in a given ELISA test, and therefore a potential food intolerance, pending correlation with the medical history of the patient.

With all food-specific IgG testing there is also a potential for cross-reactivity between related and unrelated foods, which may contain similar or homologous molecules (antigens). In addition, the closer the biological relationship between different species, the greater the degree of structural and immunological similarity of the epitopes present in the food.

Accordingly, a patient who is clinically reactive to one species will likely be reactive to the other, closely-related species due to immunological cross-reactivity of structurally related epitopes. On the other hand, cross-reactivity can also occur between biologically distantly-related species, since some protein families are widely distributed and seem to contain highly conserved structures that can serve as similar epitopes.

Finally, it almost goes without saying that the binding capacity for IgG antibodies may vary from food to food. Therefore, identical results for different foods may not necessarily imply exactly equal IgG antibody levels.

Despite all these variables associated with the interpretation of the results, it is thankfully still possible to talk of standardization of the food intolerance ELISA test itself. This is because it is possible to standardize the preparation of the food antigens, the microtiter plates and the overall protocols. We will talk about how this can be done in our final article.

Not only must ELISA food intolerance tests be standardized, they must also be reproducible in experimental terms: intra-assay, inter-assay, intra-lab, inter-lab, and batch-to-batch, with coefficients of variation (CVs) within defined tolerance limits. If the tests are automated, this will typically give results that are equivalent to an experienced manual worker, whilst removing much of the potential for human error. Typically, the ELISA inter-assay CV, whether between batches, people, or labs, should be <15%, and the intra-assay CV across triplicates should be <10%. If enough tests are carried out, say in the 10s of 1000s or more in terms of ELISA plates, it may be worth looking at automating your testing.

Challenge #4: I will need invasive patient blood sampling

Patient sampling needs to be as easy as possible for the optimal uptake of food intolerance tests. Ideally one would use a minimally invasive technique, such as capillary blood sampling. Whilst smaller panels (7-24 allergens) can use capillary blood sampling, greater blood volumes will be required for larger panels. In effect, the volumes can vary from as little as 20 - 40 μL when testing 7 to 24 allergens, to up to 1.5 mL when testing 280 allergens, so for these larger panels, a phlebotomist will be needed.

For IgG-based food intolerance tests, there is 100% concordance between plasma derived from capillary blood vs. plasma derived from venous blood.5 This means that when only a few allergens are being tested, as is often the case in the initial stages, a simple finger prick blood sampling procedure can be used, obviating the need for a phlebotomist, and even allowing patient self-sampling.

It also helps if the sample prep ahead of the ELISA testing is kept simple. Blood-based ELISA tests rely on whole blood, from which plasma (EDTA, Citrate, Heparin) or serum is prepared by a quick centrifugation step, after which the sample can be used directly in the ELISA protocol. As for all blood-based tests, serum and plasma for food intolerance ELISAs should be treated as potentially infectious. Plasma or serum samples can be stored at 2-8°C for up to 14 days, or for longer at -20°C. For capillary blood collection, heparinized tubes should be used.

Challenge #5: ELISA-based food intolerance tests must be economically viable

Ideally one needs a solution for testing that is both inexpensive and scalable, from a relatively small number of manual tests (e.g.,100s of plates) that could be carried out at point of care, all the way up to a larger scale operation (e.g., 1000s -10,000s of plates) that can be carried out in a centralized testing lab which will have the benefits of automation and economy of scale.

IgG- based ELISA food intolerance tests themselves are in theory economically viable to set up, provided they come with ready-prepared and standardized food antigens, which could otherwise be a major source of variability.

By far the greater expense comes from the fact that labs which carry out ELISA-based food intolerance tests are generally privately run and will have an associated panel of practitioners and nutritionists to advise patients on their diets and follow them up, either in person or via a reporting service. It is the personalized interpretation of the results, and the subsequent consulting which will make up the bulk of the cost for the patient, which vary wildly for a comprehensive test, from several hundred to over a thousand dollars per patient.10

Conclusions

This article has highlighted the extraordinary difficulties associated with the setting up and interpretation of IgG and IgG4-based ELISA tests for food intolerance testing. Yet the results achieved thus far leave us with hope that these difficulties are surmountable. You can read about this in our final article in the series, which includes a case study, and looks in more depth at protocol standardization and automation, finally lending credibility to the future of IgG-based ELISA food intolerance tests.

Subscribe to our blog to stay updated.

Turnkey Food Screening Solutions

Food Screen ELISAs are state-of-the-art blood tests intended for rapid, sensitive and reliable detection of food specific IgG and IgG4 antibodies involved in food intolerance reactions.

Request a quote for FS assays and get 30%** discount on your first order .

References

1. Zar, S., Benson, M. J., & Kumar, D. (2005). Food-specific serum IgG4 and IgE titers to common food antigens in irritable bowel syndrome. The American journal of gastroenterology, 100(7), 1550–1557. PubMed ID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15984980/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41348.x

2. Zar, S., Mincher, L., Benson, M. J., & Kumar, D. (2005). Food-specific IgG4 antibody-guided exclusion diet improves symptoms and rectal compliance in irritable bowel syndrome. Scandinavian journal of gastroenterology, 40(7), 800–807.

PubMed ID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16109655/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/00365520510015593

3. Canavan, C., West, J., & Card, T. (2014). The epidemiology of irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical epidemiology, 6, 71–80.

PubMed ID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24523597/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S40245

4. Velikova, T., A Kukov, A. et al. (2018). Methods for detection of food intolerance. R Adv Food Sci: 1(3): 106-119 ISSN: 2601-5412 11

5. https://www.ibl-international.com/media/mageworx/downloads/attachment/file/3/0/30131629_ifu_eu_en_igg_food_screen_7_elisa_v01_2018-12_sym7.pdf

Accessed 25 November 2021.

6. Drossman D. A. (2006). The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology, 130(5), 1377–1390.

PubMed ID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16678553/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2006.03.008

7. Engvall, E., & Perlmann, P. (1972). Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, Elisa. 3. Quantitation of specific antibodies by enzyme-labeled anti-immunoglobulin in antigen-coated tubes. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950), 109(1), 129–135.

PubMed ID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/4113792/

8. Anvari, S., Miller, J., Yeh, C. Y., & Davis, C. M. (2019). IgE-Mediated Food Allergy. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology, 57(2), 244–260.

PubMed ID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30370459/

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12016-018-8710-3

9. Jolliff, C. R., Cost, K. M., Stivrins, P. C., Grossman, P. P., Nolte, C. R., Franco, S. M., Fijan, K. J., Fletcher, L. L., & Shriner, H. C. (1982). Reference intervals for serum IgG, IgA, IgM, C3, and C4 as determined by rate nephelometry. Clinical chemistry, 28(1), 126–128.

PubMed ID: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7055895/

10. Google search “How much does a food intolerance test cost?”: https://www.google.com/search?q=how+much+does+a+food+intolerance+test+cost%3F&rlz=1C1CHBF_en-GBGB921GB921&oq=how+much+does+a+food+intolerance+test+cost%3F&aqs=chrome..69i57j0i22i30i457j0i22i30l7j0i390.9013j0j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 Accessed 25 November 2021

11. https://www.ibl-international.com/media/mageworx/downloads/attachment/file/3/0/ 30115845_ifu_eu_en_igg4_food_screen_280_elisa_v01_2018-12_sym6.pdf

Accessed 26 November 2021.

[i] The terms "IgG ELISA-based food intolerance tests" and "IgG Food intolerance" refer interchangeably to IgG and/or IgG4.

** From the list price, only for the assays available on stock

Keywords:

About the author

Nastya Yeska

Nastya Yeska joined Tecan in 2017 as a product manager responsible for the Complementary medicine product portfolio, including Food intolerance and Saliva diagnostics. Nastya is part of Global Reagent Marketing & Support Department responsible for delivering ELISA solutions. In 2021, she changed her role to Integrated Marketing Manager.